Hello, Numra from Empress Market here. If you’re new to my Substack, I write about Pakistani culture as I experience it here, at home in London, back at home in Lahore, where I grew up, and all the places I travel to that make me feel at home, through their spices and hospitality. I write about how food connects us, and I explore my ideas via my cooking. Each month (I have now stretched this deadline to the very last day!), I take an idea - a theme - and unpack it through culinary notes. In this issue I talk not about the cooking of food, but the eating of the food!

More importantly, this month we are eating with our hands. This newsletter is about the making of a Nivwala.

Seeing as it’s the beginning of the year and all, I feel this is a good place to start. Look, if I’m to teach you how to cook my desi food I need to teach you how to eat my food first.

I am not one for gate keeping. I am more than happy to share my culture with people outside of my community. My dinner table is open to everyone. I’ll even smile politely when you ask me for more naan bread or request a chai tea, but what I can’t stand is you cutting the said naan with a knife and fork and proceed to shovel rice onto it and EAT IT WITH YOUR LEFT HAND (WHAT!).

January’s issue of the Empress Market Substack is not a lesson in cooking but a lesson in desi dining etiquette.

Let’s begin with some general rules:

General Rule I:

Always wash your hands before eating. And after. I know this sounds like common sense to so many but, sometimes, people need to be told. I remember my father’s strategic announcement to the room at parties, “I am going to wash my hands”, as he always said when we made our way to the dining table. “Shall we wash our hands?” my mother asked me as a child, loud enough so everyone could hear, and I felt embarrassed. As if my own mother had thought that I wasn’t clean (probably wasn’t), but I now understand the performance we played, showing to others that we had good hygiene, whether we hosted or were guests at someone else’s home.

The solitary sink and tap installed in desi eateries (and even Nandos!) is not an ornamental design choice to emulate the motherland. Just go and wash your hands. If you’re presented with a damp towel, well done, now you’re fine dining.

General Rule II:

You’re not actually eating with your hands but the fingers. The thumb, middle and forefinger, to be precise, maneuver the meal. The food never touches the palm. Expect side eye from my mum, if you even think about lifting the plate along with your nivwala. The fingers never pass the lips.

General Rule III:

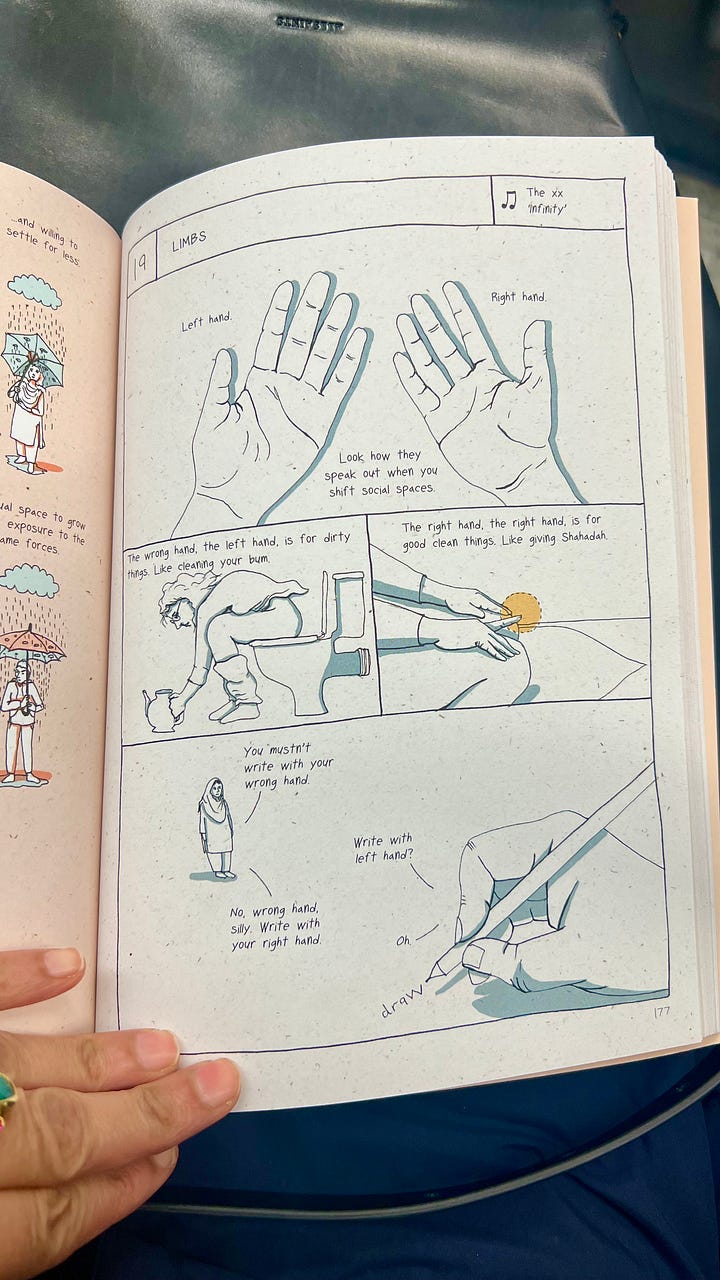

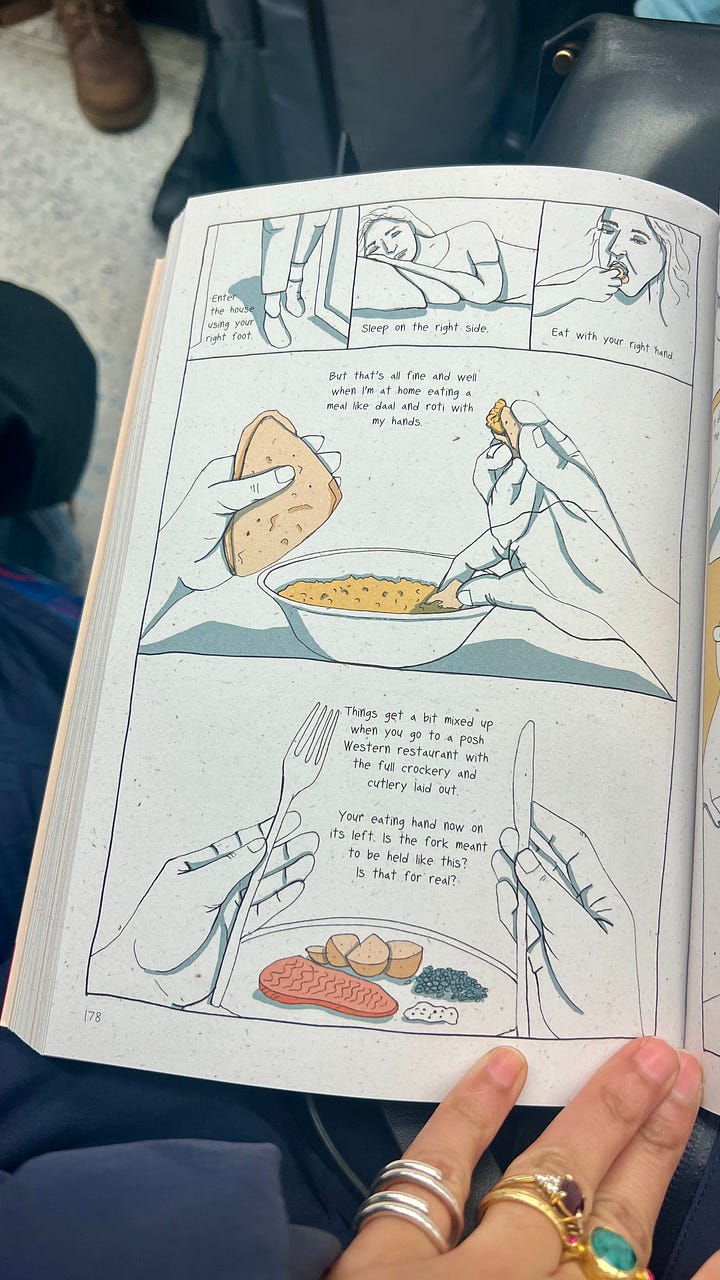

Only use the right hand to eat the food. The left hand is often considered unclean, designated only for ablution. My upbringing in the Islamic tradition, entering the room with the right foot, sleeping on the right side, writing with the right hand and, of course, eating with the right hand are all considered Sunna, the correct way. I’ve met enough left handed people who’ve told me they felt socially ostracised by this rule, some of whom were even forcibly taught how to write with their right hand. Saying that, as a right handed person, I find it uncomfortable managing my fork in my left hand. I would implore you to simply eat your food with your dominant hand!

Before we get going with some dish-specific rules, let me digress (if you’ve spent any time with me, this is something I do!), for context. I decided to write about eating with my hands after I had a conversation over dinner, as most good ideas come to be. I was recounting a dating mishap from my yout’ to Sohini, the Supeperclub chef of Smoke and Lime, about that boy I once dated who told me only ‘primitive’ people eat with their hands. He made this observation unprompted, mind you, without any encouragement from my end. I remained the Good Immigrant, silently eating my own food as he used a knife and fork to consume my home-cooked Chicken Korma with roti. The next day, I did what any sane person would do - I picked a fight about something unrelated, and we broke up.

Rule: How to eat Roti

Roti, naan, puris, all desi flatbreads are eaten by hand. You must break a piece with your right hand, using your thumb, forefinger and middle finger to measure the right amount, I’d say, roughly 2 inches in length and width. The top half folded in to create a cone of sorts, with the opening of the roti or naan swishing up whatever saalan, daal, masala feature on the plate. If you are eating meat, you should have broken the boti into a reasonable portion, or picked out the fish bones with the tips of your fingers. Any leftover sauce can be wiped off with a broken piece of roti (discreetly) before the morsel is carried to the mouth. Think of the roti as an utensil here, channeling food to your mouth, keeping your fingers clean. You must eat the roti ka nivwala in a single bite. Don’t even think of using a fork to assist you with the process. You can use your left hand to hold the larger piece of roti, to keep it warm. (Yes, I know, this violates General Rule III but if you learn anything from this newsletter today, it should be that rules are meant to be broken.)

The humble little broken piece of roti takes on a lot of responsibility in desi dining, and the etiquette around it is held in high esteem.

I’d like to point out that some specific dishes have designated flat-breads - chickpea and potato with puri and paye with kulcha, for instance. The list goes on – I could have written a whole newsletter about it! – and, trust me, if you were to serve, or to order, the wrong flatbread, there would be someone willing to point out your mistake.

What’s worse is that one time when I requested ‘naan bread’ at a restaurant - naan naan? / bread bread! - and the immediate sense of shame was so intense, I wanted the earth to swallow me whole then and there.

If you use your roti to eat rice, and the earth doesn’t spontaneously open beneath you, I’d encourage you to start digging your own hole. Double carbing is sacrilege on the desi dining table. And, still, as I type this, I’m thinking about chanaa aloo, aloo gobi, aloo ki Bhujia, so all the potato carb dishes that are designed to be eaten with a roti.

Back at the dining table, where this newsletter started brewing, my husband asked: “Why do you eat your rice with a spoon and not your hand?” I had just finished telling Sohini about my date as well; she shot me a glance while I came up with three comebacks, listed here Russ from Home Alone style:

a) eating with a spoon is a faster way to shovel food into my mouth; making a nivwala with rice is far more cumbersome. 3) You should be grateful that I’m using a spoon and not a fork, like they forced me to at my London primary school. And d) I still remember the first time someone made fun of me for eating with my hands so, as a kid, I only ate with my hands when I had to, until the etiquette eventually left my daily eating habits.

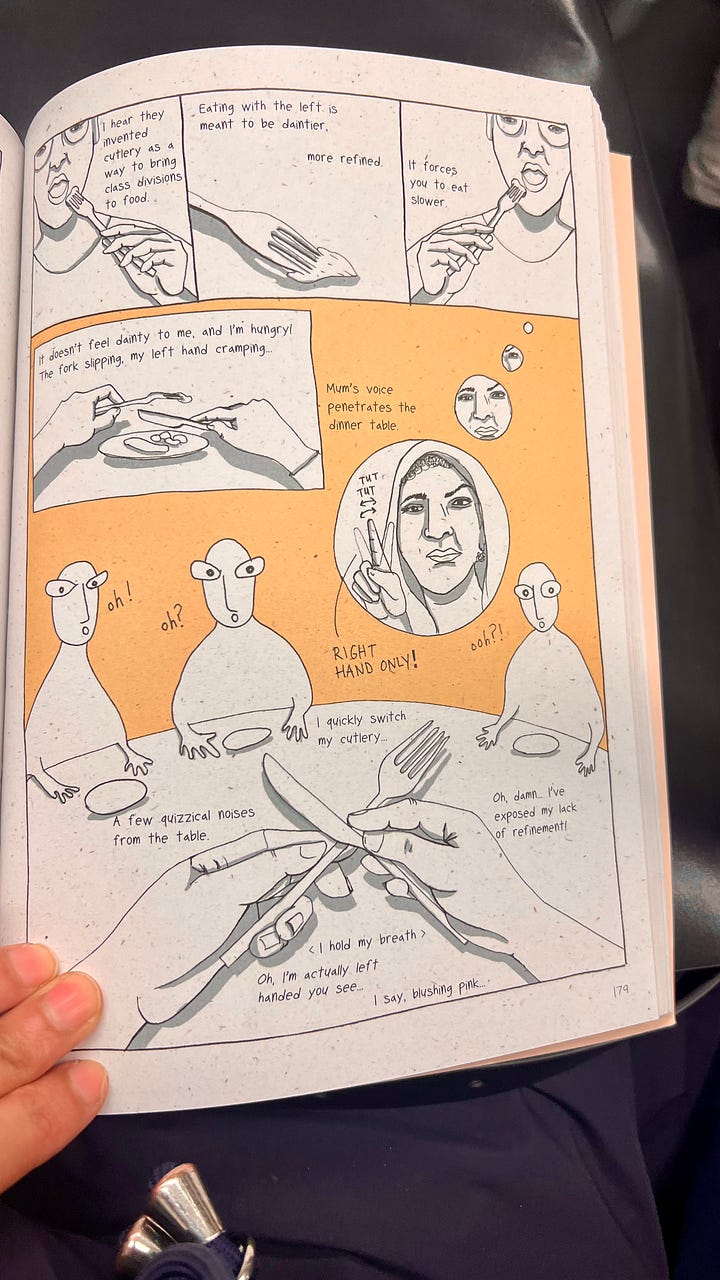

Sohini, who keeps to her West Bengali culture closer than I do with Pakistani traditions, agreed. I quote: “I only learnt how to use a knife and fork when I moved to the UK, you know. I always ate my food with my hands in Kolkata and switched to cutlery when kids taunted me at school. I still don’t hold my cutlery correctly, and people tease me when I hold my fork in my right hand!”

This shaming and, reciprocally, toxic sense of shame, have been the common denominators during my research about eating with hands. It is often the first thing that comes up in editorials about the dining etiquette and in conversations with fellow desis and chefs. We South Asians recognise how ‘uncivilised’ or ‘taboo’ the west considers eating with your hands is, that it’s “somehow primal; that clawing at food makes us look beholden to our appetites and reveals the wolf within,” writes Ligaya Mishan for The New York Times.

Listen, I hear it. Holding utensils are intended to keep our hands clean, the fork in the left less dominant hand slows the dining process down, all to maintain a sense of decorum.

As for me, I blame the manners-obsessed Victorians who deliberately concocted these rules of etiquette, mainly as a class and racial barrier to social ascension. The countless pieces of cutlery that lined their dinner plates reinforced the elitist silver cage to fortress them from the working class and the colonies. As they indulged in their meals, cadenced by one plate of food after the other, each paired with a designated set of fork and knife, they oppressed people who worked too hard to care about what fork goes where.

As much as it is pleasing to think that we as a society have broken away from these barriers, remnants of elitist rules still remain.

Cornish pasties were designed to be eaten by hand by coal miners. Pizza was a street food for the 16th century poverty stricken Neapolitans. The birth of the hamburger can be traced back to factory workers needing meals that were easy and quick to eat between shifts, as the bread filled stomachs and the minced meat was a cheaper alternative to the Hamburg steak. Even the beloved London chicken wing finds its roots in 1960’s America, as the piece of meat with the least amount of flesh, which could be sold for cheaper, if not discarded. A lot of today’s beloved pop culture cuisine finds its origin in oppression. They can only be eaten by hand, using utensils would be deemed ridiculous. Is it not surprising that they remain cordoned to the realm of ‘casual’ dining - ‘fast’ or ‘street’ food - and so can be reasonably released from formal table manners.

Serious food is still eaten properly with a knife and fork. Apparently.

Exception to the Rule:

If we have learnt anything from British colonialism, the current government’s position to support genocides etc., rules are non-negotiable unless they suit the establishment to create an exception. One such exception to eating with the knife and fork is the morsel that opens a formal dining experience, the hoity-toity canapé. This is a piece of food so expertly prepared, it’s the perfect balance of flavour, texture and ease of eating. It is designed to be eaten through a single bite, with one hand, a drink in the other (if you’re lucky), with minimal to no trickle or spill. The refinement of the canapé transcends all rules and ritual.

It’s complex, knowing what is right and wrong. Dining etiquette is engrained in all of us in one way or the other. These are The Rules presented like state guidelines that must be adhered to for fear of social ostracism. I, for one, cannot make eye contact with anyone eating with their mouth open. But then if I just redirect my energy to focus on my own manners, I can make the exception. We are, after all, all doing it wrong.

The assumption is that eating with hands “demonstrates a lack of impulse control”, says Emily Johnson at Epicurious, free of rules and refinement. My observations, conversations with friends and countless-open-search-tabs-demonstrating-my-deep-dive-near-academic-(but not quite!) research prove otherwise. Let me tell you, everyone around the world eats with their hands, and we’re all bound by our own unique decorum. Looking at South Asia alone - a vast territory spanning from Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh - I’ve found that what may be considered rude in one community, is a gesture of respect in another. We demonstrate nuances in our diversity, sacred codes of performance that are uniquely ours. ‘Good Manners’ become exclusionary terms in every community that reinforce our validity in this world. By deeming one cultural practice superior than the other, we assert our own significance. We are important. We have a right to be here.

In order to do it right, be curious and respectful, and you will win hearts.

Shahnaz Ahsan writes about how her now husband's suitability was measured against his ability to eat with his hands in the Guardian. Upon meeting the man for the first time, her niece snorted: “I bet he can’t even eat with his hands.” The man wasn’t even near a dining table, bichara. Family approval would be withheld until the suitor could maintain the most basic of Bangladeshi cultural practices.

I can fully relate to this gatekeeping. Living in the diaspora, the boundaries of our communities are stretched, and the introduction of new people into the realm must be met with relative caution. For Shahnaz’s family, being able to eat with hands correctly is a necessary reassurance that the essence of our communities prevails.

This brings me to a crucial point, especially for those of you who aren’t familiar with the rules: community is at the heart of our meals.

I invite you to check out Journey Kitchen’s blog on Bohra cuisine, and how the Bohra dinner table takes the sentiment one step forward. Artist and friend Sakina Lotia speaks of the whole family eating from the communal Thaal in her Karachi Bohra household. The extra large round platter, laden with food appears at monumental family events, where it's placed at the centre of the floor seating arrangement. Folded cross legged, knee to knee, the diners reach in, drawing morsels from the food closest to them with their fingers. Everyone eats from the same plate to strengthen the bonds amongst the household. Artist and friend Sakina Lotia reminisces about how her aunts in Karachi, who were incapable of expressing love with words, show their affection by grazing their fingers against hers during the course of the meal. They don’t look up to acknowledge the gesture, nor expressly touch hands, but they brush their fingers, only lightly, to demonstrate the love between them.

My dadi, my paternal grandmother, showed similar signs of affection during a meal. “Numra, come sit next to me” she would say, as she motioned me to the seat closest to her at the start of the meal. She pressed the grains of rice against pieces of chicken or daal, shaping them into tight balls and popped them in my mouth. It didn’t matter if I was six or sixteen, my plate remained untouched as she prepared nivwalas, for herself first, then for me, but from her own portion. I do not recall this woman ever telling me she loved me, but I felt her love in every nivwala that slid from her right hand to my lips.

Rule: How to eat rice

This is an art.

In my Pakistani home, I was taught that the food only touches the tips of the fingers, barely crossing the first digit.

According to Liz Norris, Patreon Chef of Club Ceylon in Negombo Sri Lanka, the food can come up to the second joint, the middle knuckle. Considering how important the grain is to Sri Lankan cuisine, the rice is placed in the centre of the plate, almost reverentially. The surrounding curries are delicately mixed, “like a dance on the plate - it should be graceful”. I have witnessed Liz’s gentle dance of the hand during my time with her in Sri Lanka. Her fingers never linked as they swirled the rice and curry together, without a thought, like second nature, before she drew in morsels to the mouth. “We believe when you touch the food and the textures it sends signals to your brain to get ready to receive food,” Liz told me.

This was distinct from how I was taught to eat rice in Pakistan, where the portioned saalans and rice would sit solitary on the plate, the sauce gently easing into each other as I drew nivwalas from the food closest to me.

Liz and I both agree, the rice grains should not cling to the fingers, nor should any food stain the nails or the front part of the hand. It helps if the rice is slightly tacky in touch, making it easier to create the Nivwala. The first two fingers and thumb navigate round the rice, drawing in the sauce from the saalan and wrapping lentils or meat in between the rice grains. The nivwala is delicately pressed together, reminiscent of Japanese nigiri, without a single grain breaking away as you draw hand to mouth. The ring finger may help with the lifting, the thumb sliding the morsel into the mouth.

If you were a child, and my mum was feeding you, she’d have quickly prepared these rice ball nivwalas along your plate for you to help yourself. But word of warning (and I speak from experience), there will be pataai if you lick a single finger in glee afterwards. No matter how much you enjoyed your meal, you should not lick your fingers.

Making a nivwala by hand really forces me to consider the food I am eating. Rather than shoveling ingredients with a spoon or fork, I am made to consider the flavours and textures I want from each bite, and how large a portion I can manage. It slows down the meal, as I take my time to form each nivwala. The performance is even appreciated as a proof of good dexterity. My mum goes as far as encouraging my nani, her own mum, to eat her rice with her hands to strengthen the muscles in her old frail hands.

The experience of eating with hands connects us with our food in a way cutlery could never do. We check for temperature, for ripeness, manage the texture, picking out bones and whole spices. Nothing is worse than biting into a whole black clove after all. Our fingertips connect us to our food as we caress each nivwala and anticipate its flavour. It is a sensual experience, both intimate and personal.

As a last anecdote, let me tell you about experiencing Omakase at Rai, the Japanese restaurant off Charlotte Street. True to Japanese fine dining, the chef bids the diner to eat their Nigiri by hand. And with only the sushi counter between us, Chef Padam Rai passed the delicate nigiri directly from his hand to my hand, and I drew it to my lips. The rice was so delicately packed, it would have fallen apart if it had been handled with chopsticks. Each one of the courses I ate was prepared only seconds earlier, just for me, from the maker's hand to mine. The gesture felt so intimate, it made me wonder if it was appropriate for the other diners to witness it.

Sitting in a Japanese restaurant in the heart of London, I was reminded of how eating by hand connects us. It is not limited to my South Asian community, but as far as Japan, and as close as home, here in London. I think of the intimacy of how my Dadi would feed me. The love in my mum’s nivwalas, her own balls of rice, lined up on my plate for me to eat. It connects me to all the other dawats I’ve indulged in, as we sit together to eat, sharing a common meal. I learn from each experience, watching how others eat their food and develop my understanding of different culinary traditions.

In this way, my soft finger pads connect me not just to my food, but to all the meals I have eaten, and all the cultures I've had the privilege to learn from, a history carried in my finger prints.

Numra x

If you enjoy this newsletter, feel free to share it with friends.

PS. head to my website for more recipes and to learn more about my catering and supper clubs.

Don't tell that to Lebanese who scoop up rice with bread 😅