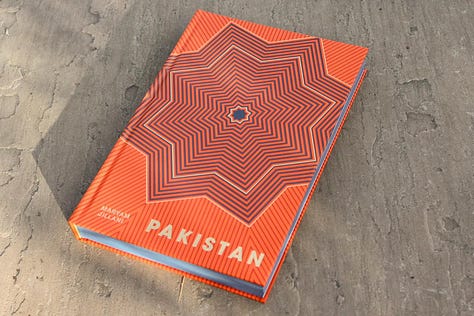

A very important cookbook was published this month.

Pakistan, written by Maryam Jillani, is noted to be the first comprehensive cookbook about our homeland’s culinary landscape. With over 100 recipes and essays about Pakistan’s regions and major cities, Maryam documents the cuisine in a way that has never been done before at this level. This effort of hers is outstanding, not only for covering the sheer geographical scale of Pakistan so comprehensively, but also in the craft of writing recipes themselves. In order for the recipe book to be good, the recipes must be accurate, accessible, and a worthy historical record of Pakistan and its cooks.

I wait for my copy of Pakistan, the cookbook, with bated breath as my pre-order arrives any day now. I know I will be reading Maryam’s book, almost academically, as a way to improve my desi cooking as well as better understand my people. I trust in her writing from her early days writing her blog and now substack, Pakistaneats, to the various publications she has contributed to. Maryam even shared her recipe for chapli kabab in my own newsletter a few years go and I’ll tell you, her measure of spicing and the accessibility of her method made cooking her kababs a joy!

I spoke to Maryam about her process of writing her book and we bonded over the challenges of recording recipes. “I found that even if I observed a cook prepare a dish and took copious notes on the timing and measurement, the dish would not turn out exactly the same way in my own kitchen, “ she says. “Factors like your stove and cooking utensils make a big difference, and when you are writing a cookbook that strives to provide recipes that are accessible and replicable, you have to make sure you are also guiding readers on doneness cues.”

The publication of such a definitive cookbook about Pakistan makes me contemplate about how I conjure up menus at Empress Market and the way in which I embrace my heirloom cuisine. I’m a firm believer of not following a recipe, free pouring, smelling my way through the cooking, or simply calling my mum if I need guidance.

It is only when I sit down to write about my food and the work that I do, that I am preoccupied with finding the right words to describe the dishes and how to cook them. It’s much like the process of learning how to cook the dishes themselves. I write and I re-write in order to cook well.

HOW I WRITE. HOW I COOK.

My food exists in the realm of the unwritten.

I begin with cooking heritage recipes from my Pakistani and Indian background. These are very much part of an oral tradition, conversations with my mum that start with “acha sunnau” and continue with skeletal instructions and ingredients listed on the digits of mum’s right hand. My understanding of the recipes passed down through generations of my family is an ongoing process. I am resigned to knowing I will make mistakes along the way, it’s ok. The determination of getting it right is what keeps me going as I cook the dishes repeatedly. Mum’s totkas in the kitchen are certainly my guiding force. The special tricks to cooking Pakistani food are the milestones I need to hit as I recreate the recipes from where I am from.

This sort of intuitive cooking, passed down through maternal bonds, is quintessential to Pakistani kitchens. Maryam also points out, “South Asian cooks learn to prepare dishes by watching their mothers and grandmothers, and by engaging their senses.”

She extends this mentality of handing a recipe down, into her style of writing as she tells me, “I also wanted to strike a balance between showcasing the diverse recipes as I found them in Pakistan with ones that people all over the world can easily recreate (and want to prepare) in their own homes. So most of the recipes are adaptations of original recipes based on feedback from a wonderful team of voluntary recipe testers, and my own experience and palate.” I have also heavily pushed back on the idea of "authentic" Pakistani food or "authentic" recipes because I do find that recipes vary widely across generations, regions and even households within the same neighbourhood. I hope this will empower cooks to play, and adapt every recipe based on what works for them.”

A recipe changes in the hand of every person that cooks with it. A good recipe is beyond a rigid set of rules, but a guide in the kitchen with which to play with.

This is really how I like to cook at Empress Market. I let the flavour in my own hand guide me to where I need to go. I tap into my memory of how a dish should taste or what makes sense to Pakistani cuisine. Eventually I’ll get there and only a taste test courtesy of my mum and nani will sway the decision of success or failure. Those fatal words, “acha hai, magar”, after the first bite are weighted and lay heavy on the heart. Over time, I’ve learnt to let these words go and I take them as a general guide to lead my role as a chef. I know my cooking can be good, yes, but there is always room for improvement and growth.

Then there are the dishes I make up along the way.

My personal style of cooking at Empress Market is also a result of eating a good meal from a place that may seems unfamiliar. I often find myself deconstructing a dish that I’ve enjoyed, first by fiddling with it with my fork, as the plate still sits in front of me. Then I spend too much time thinking about the ingredients and how they came together. Sometimes, I may not have even eaten the food, but spotted a picture of something I’d like to eat (and cook!) on instagram. I save it for later to look back at and recreate myself. I can deep dive researching the cultural place of these dishes for days! It’s important for me to grasp where the food comes from. This is the only way I can identify my connection to the food and people of other cultures, and bring them closer to me.

All these factors overlap when I design the menus at Empress Market events. I think of the season, the occasion. I ponder about how to showcase my culture on a plate. Nostalgia is key, as I yearn to retell the story of my childhood through the flavours and the feel of a time that feels far away. And finally, I think of my role in the world today, as I connect to ingredients and styles of cooking beyond the place of my birth and upbringing.

The recipes for the dishes I cook come together in the kitchen. They might not work and I won’t serve them. And when they do, you’re the lucky one to eat my food at an Empress Market dawat.

This is how my Suji ka Halwa recipe came about.

THE STORY OF SUJI KA HALWA

Roasted semolina, stewed in jaggery and cardamom infused ghee. This is Suji ka Halwa. There is a warm nuttiness that comes from the halwa, pairing nicely with the floral cardamom. It’s creamy, almost buttery when eaten warm, and a grainy set pudding when served cold.

Suji ka Halwa is the perfect example of how store cupboard staples come together to create a dish that is both humble and indulgent.

I’m endeared by the number of cultures that exalt semolina halwa as a classic dessert on their dinner tables. In Turkey, there is the famous irmik helvası standing out as a staple dessert. Pine nuts are the distinguishing characteristic of this Turkish semolina halwa and it is served like a set round dessert, sometimes with a creamy centre filling. In Palestine and Lebanon, there is Layali Lubnan (Lebanon nights!), an extravagant two layered semolina pudding. A milk and semolina style halwa is topped with whipped cream and finished with orange blossom syrup.

In South Asia, Suji ka Halwa goes by many names. Mohan Bhog in West Bengal, Rava Halwa in South India.

In Pakistan, every occasion calls for Suji ka Halwa. It is served at shaadis, basant, dinner parties and even at funerals to remember the departed with a taste of something sweet. It can be centre stage on an Iftar spread during Ramzan, thrown together last minute when unexpected guests rock up, when you fancy something sweet to eat after dinner, or even as a midnight snack why don’t you.

Suji ka Halwa is not just a dessert. It has main course energy, best served alongside chanaa aloo and puris as a desi brunch. I can hear you heathens turning your nose up at this combination but trust me, it works so well together. You break a piece of the greasy puffed bread to scoop up the spicy super savoury chickpeas and potato, along with a pinch of sweet halwa - this is the perfect nivwala.

There are many ways to cook Suji ka Halwa. And there are countless occasions it can be eaten. I’m always surprised by how fast the halwa works its magic, how quickly the pantry ingredients come together, 20 minutes at best, to be served as the perfect dessert.

Suji ka Halwa has a place of affection in every home. It belongs to all of us. There is a recipe written for everyone. And there is comfort in knowing that alone.

RECIPE

NUMRA’S SUJI KA HALWA

I served Suji Ka Halwa with Chanaa Aloo and Puris at my I♥️LHR supperclub last month. I am sharing this version of Suji ka Halwa with you today. This is my recipe.

Serves 4. Maybe 5 if you’re lucky.

My Suji ka Halwa recipe highlights the technique required to get the correct texture and flavour of a desi halwa. I have saved the recipe for my mum’s classic Suji ka Halwa recipe in my instagram highlights if you’d like to take a gander.

My recipe is a vegan version, cooked with coconut oil. I’m not even remotely vegetarian, but I love to find ways to make classic Pakistani cooking more inclusive and plant based.

I am also a offering a way to add a bit of extravagance to the humble dessert by crumbling khoya and whole maple candied almonds over the top. Khoya is a dairy milk reduction served with desi desserts. There is an art to making khoya, cooking full fat milk for what feels like an eternity to a crumbly dairy paste, all the while, without burning the proteins. I am making my khoya with cashew and coconut milk powder in my recipe, which is way faster, and plus now it’s vegan.

I’ve written my Suji ka Halwa recipe the way I’d expect a good recipe to be written. There is more detail than my mum would give. I’ve included her totkas, of course, along with the lessons I’ve learnt myself over the years of serving this halwa.

After you’ve read the recipe here, I want you to cook my Suji ka Halwa without measuring the ingredients or referring back to my written method. I want you to free pour, use your intuition, make mistakes and make a Suji ka Halwa that belongs only to you.

INGREDIENTS

1 unit coconut oil (heaped 1/4 cup / 125g)

1/2 stick cinnamon

2 cardamom pods

2 units fine semolina (1/2 cup / 250g)

1 unit desi gurr (this can be adjusted to taste. A heaped 1/4 cup / 125g)

A splash of kewra essence (1 tsp)

half the pack of coconut milk powder (75 g)

1 unit finely ground cashew (half the bag from my local grocer / 125g)

Some maple syrup (1 tbs? I really I can’t remember how much I used because I free poured this one)

Generous handful of whole almonds

METHOD

1. Toast the spices in the Coconut Oil. Melt the Coconut Oil on a low to medium heat with the cinnamon and crushed cardamom pods. Let them sizzle, for a few seconds at best.

2. Roast the Semolina. Stir the semolina into the oil until the grain turns a golden brown and release a nutty aroma. It’s important to keep stirring so the semolina doesn’t burn!

3. Dissolve the gurr in water. In another pan, dissolve the gurr in 500ml of water.

4. Mix the gurr water and semolina together. Pour the sugar solution over the toasted semolina. The semolina will immediately soak up all the water and double in size. You can add a splash more water if you like your halwa creamy, a polenta like consistency!

5. Cook. Continue stirring and cook the halwa for another ten minutes until the oil reveals its sheen and the halwa begins to peel away from the edges of the pan (bhunnai!).

6. Adjust for sweetness. You can taste the halwa for sweetness at this stage and add more gurr if you like your halwa sweeter. Remember, the sweetness settles down as the halwa cools.

7. Turn off the heat. Drizzle a splash of khewra and the halwa is ready!

8. Khoya. To make the khoya, pour the coconut milk powder and ground cashew in a pan on medium heat, with 60-100ml of water, until they come together to form a paste. The khoya will set as it cools.

9. Candied Almonds. Toast the almonds in a dry frying pan and drizzle over the maple syrup. Pour the almonds over a piece of parchment. Crush some of the almonds for colour and texture.

10. Serve. I served my Suji ka Halwa warm, the khoya crumbled, almonds sprinkled over. It pairs well with the Chanaa Aloo from February’s Empress Market newsletter.

LOVE THIS AND THANK YOU 💙